“You wake up in the morning, rinse your mouth, you drink a liter of water in small sips, and have a breakfast with a single type of protein” – these were Matei Bejenaru’s tips, when he saw me in the morning, rather hungover and shaky, like a sugar cane on the day’s forklifts, in the hotel lobby prepared for us, the guests invited to his opening exhibition by the Kunsthalle Bega collective. More than just an atmospheric introduction, which increasingly stylistically punctuates the typology of Western cultural journalism, especially American, these are useful tips for anyone, not just those dehydrated by the spirits of a minor flâneurism, and in their algorithmic precision, the sincere care, outline both Matei Bejenaru’s human typology and, as is happily is the case with all authentic authors, his artistic one which we will discuss here.

Bejenaru, so difficult to formally or conceptually to pin him down in a unified formula – the public having to deal so far in his career with two Matei’s, the performative-social one and now, the technophile till the opposite end, of poetry; or with Matei the artist, and Matei the curator – seems that in the last 15 years he has settled down into the specificity of the “mirror with memory” medium [just one of the formulas used at the appearance of the camera in the mid-19th century, but which says so much about what it replaces], more precisely into a “0 degree” of photography, as the recently concluded exhibition aptly captures. A photography about photography – about its products, mechanisms, processes, surfaces, lines, and shadows. I adapted this term to use it differently from the minimum of structural & material imposed by Alexander Rodchenko, into a minimum of representation. As in modern painting where the questioning of the surface (re)discovers compositionally the grid [matrix from which any image is formed], Bejenaru’s material extra-technicality in photography actually attracts the opposite, pictoriality. When the image is rendered so concretely and immersive as here, a strange pictorial tension is produced through the extra contour & saturation of the captured light.

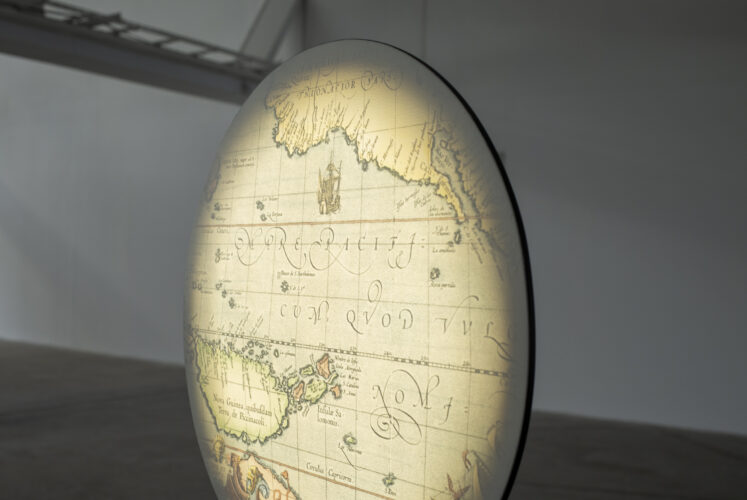

Delimiting between these two periods, how strange “L’air du Temps” (1996) must have seemed in the creation of the first Matei, which, sean from today’s perspective, appears not only as an emblematic-defining work but also strangely suited to this boolean immaterial times. And speaking of Matei the man, in the exhibition at Kunsthalle Bega, the choice of slide projection technique, on par with that of printing images, obviously also betrays the academic inclination of the professor Bejenaru. The slides were auxiliary elements of academic disciplines long before the advent of screens. Personally, I still seen them, in the mid-’90s. Historically, after the introduction of photographic plates in the second half of the 19th century, the “magic lantern with slides” became an instrument especially recommended for educational purposes. I refer, of course, to that Laterna-Magica-Bilder, the first type of projector, which, with the advent of photography, replaced manually rendered images with those reproduced mechanically & chemically, a palpable echo found in the work formed by a slide projection on a circular surface, placed circularly in the exhibition trajectory, and thus ending the circuit proposed by curator Cristian Nae, also started with a slide projection.

This, which also gave the title of this review from the sensation I had in front of it, is placed in the first room of the Kunsthalle Bega space, also called “the box” [often dedicated to small individual projects]. Here, three medium format slide projectors were placed in the background of the room, projecting intermittent material images – like photons you can feel on your tongue. With a heavy corporeality, a kind of light materiality, is a sensation I also had when I first entered a room-sized camera obscura. There, besides the spectacular living shadows appearing unmediated by mechanical or electric means, the strong sensation you have is the concreteness of the information carried by a light beam. The same sensation you have in front of the projections in here. And it’s not just about their formal quality, but about what Bejenaru chooses to represent, often leaving room for strong verticals and horizontals, for details in zoom in and out, for representing the same subject in three different perspectives, both spatial as temporal, which strengthens the effect of the real in these illusions. Sometimes images of extra technical rigor, other times of banal or formal aesthetic. The phenomenon triggers a strange bodily experience even if we are talking about a beam of light that projects immaterial images. In the exhibition, the slides are just another example of “opticity” besides the large-dimension printed photography, monitors with projections hidden as in a Trojan horse structure, the discreet black curtain referring to another technophile work, video this time, “From A to C”.

The exhibition path continues with negative photographs on film, representing cameras of medium or large format. Printed on industrial dimensions and placed on the verso and recto of monolithic boxes, these images recall the chemical recording of continuous light gradients on a chemically treated paper, the standard of a analog image. Complementary to that 0 degree in Bejenaru’s photography, there is also a democratically exhaustive representation of subjects: ancient statuettes, maps, urban corners of a minor quotidian; objects, artifacts, things, and rarely complicated human individualities, as if wanting to impose this reality of the mechanical-chemical recording device of reality, territorially over the entire order of the world. If generally photography is understood as the recovery of a subject from all possible ones, Bejenaru seems to want to safeguard the entire world through his lens, not to miss a corner, thus even documents, sculptures, artifacts from other genres and mediums must also pass through the mirrored filter of the device.

Conversely, but complementary as I said, the 0 degree is that “message without a code” theorized by Roland Barthes in “The Photographic Message” (1961), the opposite pole of Bejenaru’s social projects, but so overwhelmingly rendered, authentic, total, and personal altogether. Through these photographs about photography, Bejenaru explores the social spaces of an obsolete media technology, extending its multiplicity structure from the technical production of generated copies, to an authorial aesthetic based on media archaeology. If today the post-medium condition predominates, for him we talk not of medium specificity but rather of a fetish-medium. Also, the projector/projection, not only are more relevant than ever today, in the world of ubiquitous screens, but they outline “information” in a kind of final readymade. These aspects betray a romantic typology, a melancholic contemplation of these media artifacts that function by eliminating the social and historical context, to make the photographic technology the undisturbed object of his attention. This treatment of the photographic object at a high technical level in Bejenaru reminds me of the angelic mirror theorized by Athanasius Kircher. He develops the theory of the two mirrors, where one is the human mirror, suffering refractions and distortions, and the other, the angelic one, a “spotless” surface (reflecting divine light).

Although I have ruled out as dissociative the social-performative dimension with the technical-fetishistic one in Bejenaru’s work, I believe there is a vital point where they entangle, more precisely the second being a consequence of the first. This technophilia is, I believe, a generalized and natural reaction of the entire transition society from the 90s Romania. Precisely because technology [the newer the better, and what other field renews more often than this?] represented the avatar of evolution in our society, of the savior west that never came, but in which we got finally, to take their products and send them home. For Bejenaru, the brands of the represented devices, of the running projectors, the ambition of the constructions, and the quality of the photographic printing are among the professional gear or, if we were to use marketing terms, the premium one.

The solo show “PROIECȚIE 02” by artist Matei Bejenaru, curated by Cristian Nae took place at Kunsthalle Bega, Timișoara between 12.04 – 08.06.2024.

POSTED BY

Horațiu Lipot

Horațiu Lipot (b. 1989) is a curator and cultural manager. He worked as the art director for IOMO gallery during 2021 and Atelier 35 gallery during 2019-2020. In 2017-2019 he was the coordinator for ...

Comments are closed here.